Vacuum Molded Plastic: A Designer’s Guide to Rapid Prototyping, Material Choices, and Production Readiness

Vacuum molded plastic sits in a practical middle ground in the design process. It is more honest than early concept models, but still faster and more flexible than full production tooling. For designers balancing creative intent with real-world manufacturing limits, it offers something especially valuable: fast feedback that behaves like production without the cost or commitment of production.

Unlike 3D prints that assume perfect thickness, foam models that ignore structure, or CNC models that remove material rather than form it, vacuum molded plastic responds to heat, gravity, stretch, and material flow. Those forces expose how a design will actually behave when it leaves the screen and enters the factory.

This guide is written for designers who are already comfortable with basic prototyping methods and want deeper insight. It focuses on what vacuum molded plastic reveals during real projects, how it affects geometry and material decisions, and where it quietly determines whether a design moves smoothly into production or struggles once scale is introduced.

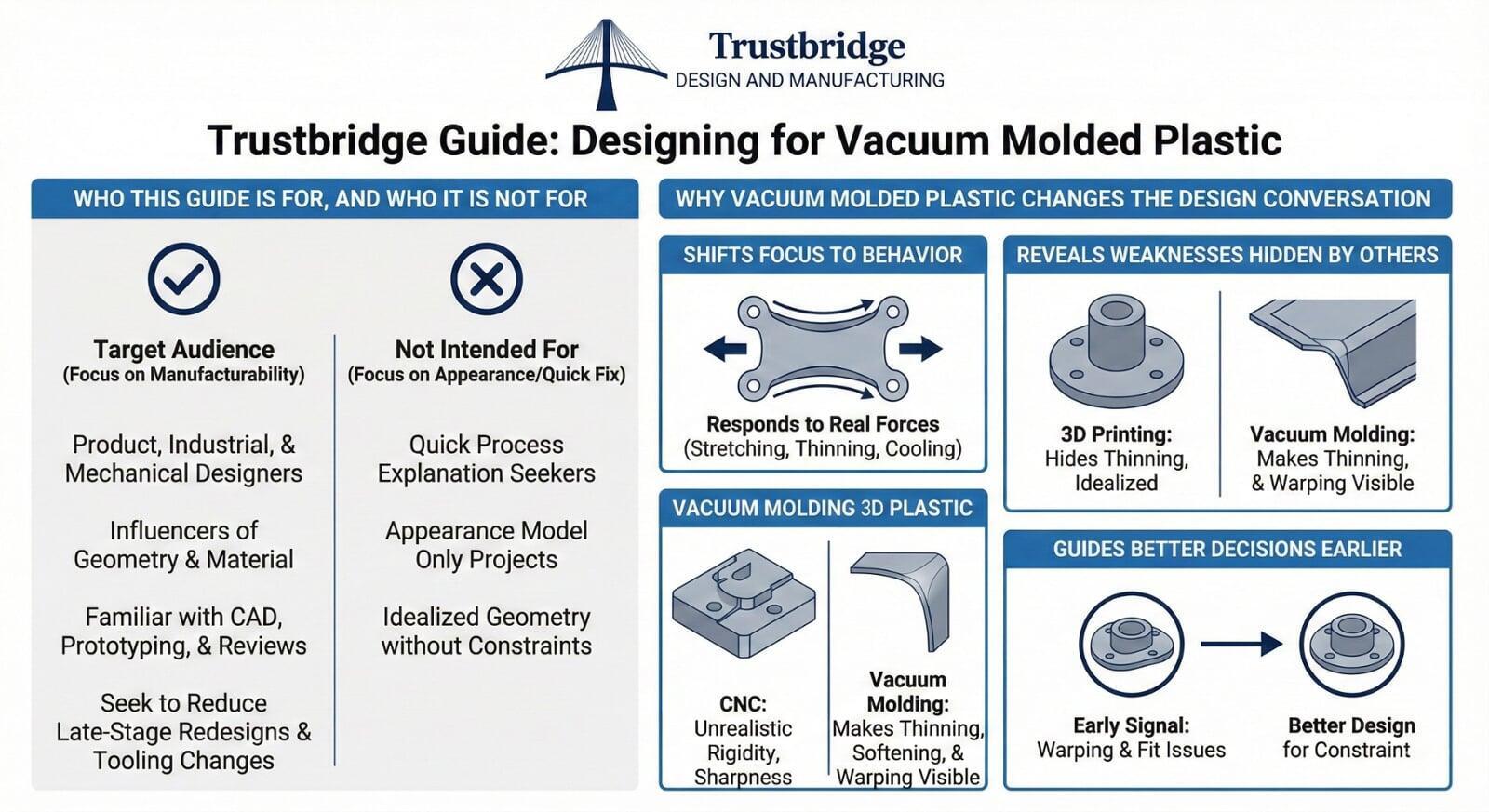

Who This Guide Is For, and Who It Is Not For

This guide is for product designers, industrial designers, and mechanical designers who influence geometry, material selection, and manufacturability—not just surface appearance. It assumes familiarity with CAD, basic prototyping workflows, and cross-functional reviews with engineering or manufacturing teams.

It is especially useful for designers who want to reduce downstream surprises—things like late-stage redesigns, assembly issues, unexpected flexibility, or tooling changes that appear only after money and time have already been spent.

This guide is not meant for teams looking for a quick explanation of vacuum forming as a process, nor for projects where appearance models are the final output. The value of vacuum molded plastic shows up when designs must survive tooling constraints, assembly requirements, inspection, and repeatable production conditions.

Why Vacuum Molded Plastic Changes the Design Conversation

Vacuum molded plastic changes design conversations because it shifts the focus from how a part looks to how a part behaves. Parts formed this way respond to real forces—material stretching, thinning, cooling, and gravity—that closely resemble early production behavior.

Where 3D printing often hides thinning and stiffness problems, and CNC models suggest unrealistic sharpness and rigidity, vacuum molding makes weaknesses visible. Designers begin to see where wall thickness drops in deep draws, how sharp radii soften, and where large flat areas lose tension or flex under light load.

For example, a corner that looks clean in CAD may thin unevenly during forming, causing unexpected softness. A long flange that appears flat on screen may warp slightly after cooling, affecting fit. These are not flaws in the process—they are signals that guide better design decisions earlier.

Vacuum molding does not reward idealized geometry. It rewards geometry that understands constraint.

Trustbridge Tip 1: Accuracy Mindset Before Production Pays Off

Design accuracy is not just a quality concern later in the process, it begins with how designers think about features before manufacturing starts. Vacuum molded plastic reveals how geometry behaves under heat and form, but the biggest insights come when designers think about accuracy early. This includes considering which surfaces and dimensions truly matter when the part is made, and validating those through prototypes that exercise real part behavior rather than just visuals.

This mindset aligns well with approaches that ensure part accuracy before production begins. By intentionally focusing on functional surfaces and measurement-critical features early, designers reduce downstream surprises and elevate the maturity of early prototypes.

Rapid Prototyping as a Learning Tool, Not a Speed Metric

Speed is often highlighted as the main advantage of vacuum molded plastic, but for designers, learning speed matters more. Learning speed means how quickly a prototype shows what works, what fails, and what needs adjustment.

When vacuum molding is used only to check appearance, its value is limited. Its real strength shows up when parts are tested for fit, stiffness, and interaction with surrounding components. If a part connects to multiple components, vacuum molding quickly reveals misalignment, tolerance stacking, or unexpected flex during assembly.

For instance, a mounting flange may interfere slightly with a neighboring part, or a snap feature may feel too soft once formed. These issues are easier and cheaper to fix at this stage than after tooling is locked.

Unlike rapid prints that allow sharp edges, uniform walls, and unrealistic rigidity, vacuum molded parts push back. That resistance is useful. It teaches designers where assumptions break down before production does.

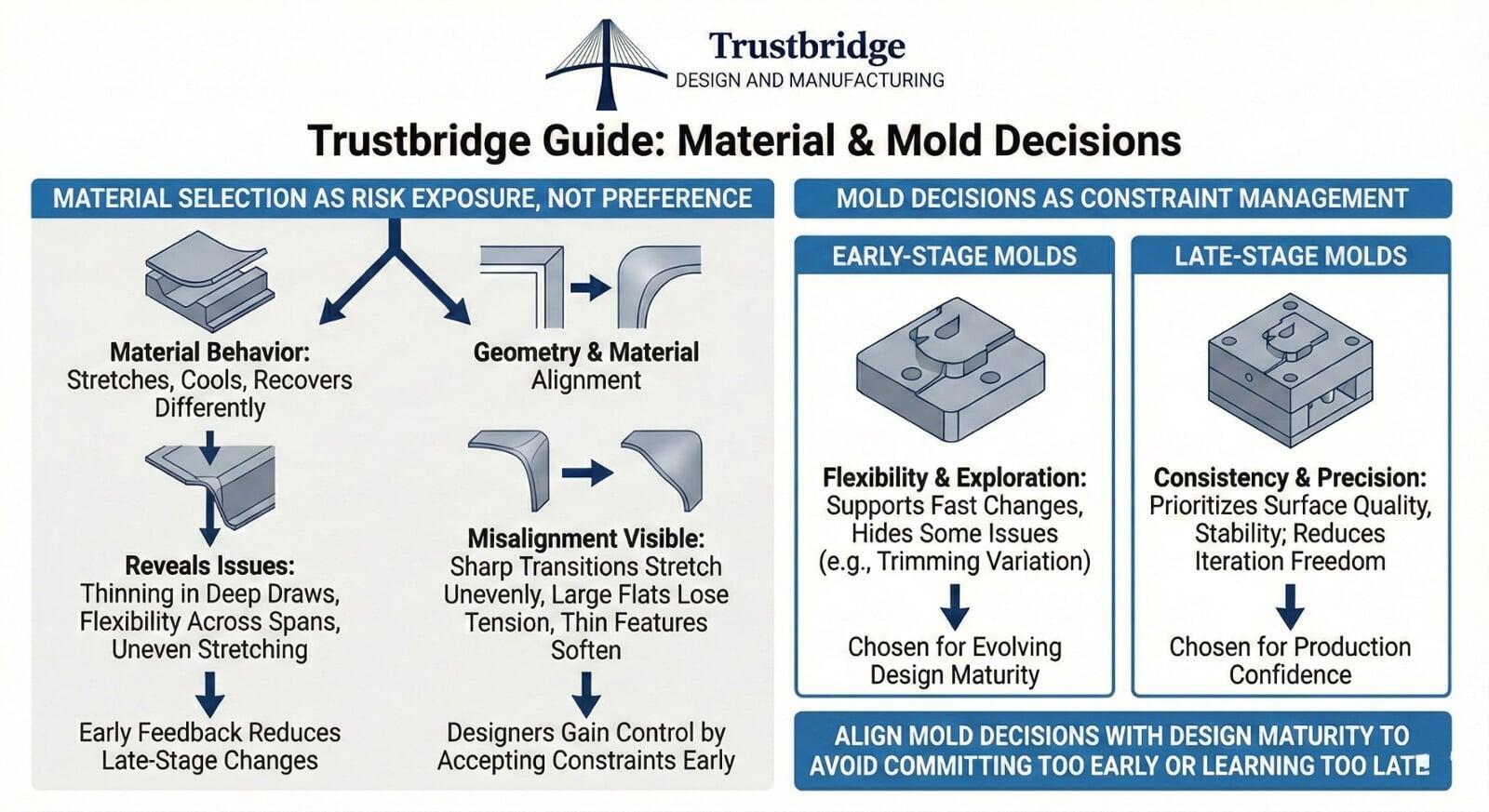

Material Selection as Risk Exposure, Not Preference

Material selection in vacuum molded plastic is not about choosing what looks best on a datasheet. It is about exposing risk early—before geometry, tooling, and timelines are locked in.

Different thermoplastics stretch, cool, and recover differently. A material chosen for surface quality may thin aggressively in deep draws. Another may hold shape well but become too flexible across large spans. These behaviors often appear around corners, over tight radii, or near localized features.

This is where vacuum molding becomes a diagnostic tool. It shows whether material and geometry actually work together. Designers who respond to this feedback early reduce the risk of late-stage changes driven by performance failures instead of design intent.

Material choice becomes a decision with consequences, not a handoff.

When Geometry and Material Disagree

When geometry and material are misaligned, vacuum molding makes it obvious. Sharp transitions stretch unevenly because material must travel farther. Large flat surfaces lose tension as heat relaxes the sheet. Thin features soften because there is not enough mass to retain stiffness after forming.

If draft feels optional in CAD, it becomes mandatory in forming. Digital tools allow perfect shapes. Physical processes do not.

Designers who accept this early gain control instead of compromise. Forms begin to cooperate with material behavior rather than fight it.

Mold Decisions as Constraint Management

For designers, molds are not just tools—they determine how much truth a prototype can tell. Early-stage molds are typically simple and flexible, supporting fast changes and exploration. Late-stage molds prioritize consistency, surface quality, and dimensional stability.

Early molds may hide issues like trimming variation, draw inconsistency, or subtle warping. Later molds reveal these details but reduce the freedom to iterate.

Understanding this trade-off helps designers choose molds based on design maturity. When geometry, interfaces, and material choices are still evolving, flexibility matters. When confidence is needed before production, precision becomes the priority.

Designers who align mold decisions with design maturity avoid committing too early or learning too late.

Trustbridge Tip 2: Know When Prototyping Stops Reducing Risk

Prototyping is supposed to reduce risk, but it stops doing that when iterations stop providing new information. Designers sometimes continue refining early models not because they are uncovering real performance insights, but because they are chasing diminishing visual returns. Vacuum molded plastic exposes physical behavior, but the real signal occurs when prototypes stop revealing meaningful insights about function, form, or assembly and start only refining how a part looks.

This point where prototyping shifts from risk reduction to delaying production decisions is critical. Recognizing it allows design teams to move forward with confidence rather than extend iteration with low-value adjustments.

Designing the Transition from Prototype to Production

Vacuum molded plastic plays its most important role during the move from prototype intent to production intent. This is where small compromises—draft angles, corner radii, stiffening features, trimming consistency, and cooling behavior—start to matter.

Designing for production does not mean limiting ambition. It means shaping ambition so it survives reality.

Designers who use vacuum molding to test these compromises early avoid costly rework later.

Manufacturing Lead Times as Design Sequencing Tools

Lead times are often treated as external constraints, but they shape how design decisions should be ordered. Vacuum molding shortens the feedback loop between change and consequence.

This allows designers to lock critical interfaces—such as mounting points, clearances with neighboring parts, datum surfaces, and structural ribs—while leaving cosmetic details open longer. When used intentionally, vacuum molding prevents teams from rushing decisions that are not ready to be finalized.

The result is steady momentum without blind spots.

Recognizing Design Red Flags Early

Certain patterns suggest vacuum molded plastic is being underused. If prototypes are approved without assembly testing, learning has been delayed. If parts require repeated trimming adjustments, geometry issues are being pushed downstream.

Other red flags include inconsistent wall thickness, unpredictable forming lines, reliance on one-off “hero” builds, or parts that assemble only with force.

These are not obstacles. They are signals.

Vacuum molding does not create problems—it reveals them while they are still fixable.

Trustbridge Tip 3: Pairing Physical Feedback With Better Design Decisions

Physical feedback from vacuum molded prototypes is valuable, but combining that feedback with structured design analysis deepens learning. For example, integrating physical insights with methods that help quantify stress, deformation, or load behavior allows designers to see beyond surface variation and focus on functionally critical issues.

This combination of real part feedback and analytical decision tools helps teams make better design decisions that hold up in production and align with engineering intent.

Collaborating with Manufacturers as a Design Extension

The strongest results appear when designers involve manufacturers before designs are finalized. Early conversations about draft, material behavior, tooling assumptions, and inspection methods sharpen decisions instead of limiting creativity.

Clear intent matters. When designers explain what features are critical, where flexibility exists, and what risks are acceptable, manufacturers can offer constraint-based feedback that improves outcomes.

This collaboration produces prototypes that inform decisions—not just represent ideas.

Conclusion

Vacuum molded plastic is most powerful when designers stop treating it as a stepping stone and start treating it as a lens. It reveals thinning patterns, deformation, forming behavior, assembly interaction, and material limits—while change is still affordable.

Designers who internalize real-world constraints early build products that survive beyond the prototype phase. Vacuum molding is not optional in that journey. It is instructive.

If vacuum molded plastic is already part of your workflow, revisit how you use it. Look for signs of deferred learning: excessive trimming changes, unexplained deformation, inconsistent forming lines, or assemblies that work only with force. Bring manufacturing voices into design reviews earlier—not to restrict creativity, but to sharpen it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What makes vacuum molded plastic different from other rapid prototyping methods?

Vacuum molded plastic behaves much closer to a real production part than most early prototypes. Unlike 3D printing or foam models, it responds to heat, gravity, and material stretch. This reveals thinning, deformation, and stiffness issues that digital models and additive prototypes often hide.

2. When should designers choose vacuum molded plastic instead of 3D printing?

Designers should use vacuum molded plastic when geometry, material behavior, or assembly fit needs validation. While 3D printing is useful for early form exploration, it often produces unrealistic wall thickness and stiffness. Vacuum molding shows whether a design can survive real forming and manufacturing constraints.

3. How does vacuum molded plastic help designers identify production risks early?

It exposes where designs are fragile before production tooling is committed. Deep draws may thin unevenly, sharp corners can soften, and large flat areas may lose tension. Catching these issues early reduces late-stage redesigns and tooling delays.

4. How does vacuum molded plastic support the transition from prototype to production?

Vacuum molded plastic helps designers validate draft, radii, wall thickness, and part interfaces under realistic conditions. This ensures design decisions hold up when moving into production processes like injection molding, reducing rework and improving production readiness.