When to Switch from Prototype to Production (and How to Know You’re Truly Ready)

The transition from prototype to production is rarely marked by a single moment of certainty. For industrial and product designers, it often feels like standing on a fault line. On one side is creative freedom, fast iteration, and forgiving prototypes. On the other is scale, constraint, lead times, and irreversible decisions.

The cost of waiting too long is rarely visible upfront—but it compounds fast. Missed launch windows, rushed tooling decisions, and supplier rework can add months and significant unplanned cost. Most design failures do not happen because teams move to production too early. They happen because teams move too late, mistaking continued refinement for progress.

Designers are trained to iterate, refine, and improve. That instinct serves products well in early stages. But there comes a point where additional prototype iteration no longer reduces risk. It quietly increases it. Tooling costs rise. Schedules compress. Suppliers lose patience. Design intent begins to erode under pressure. Knowing when to switch is not about perfection. It is about readiness.

This blog is written for designers navigating that exact moment. It explains how to recognize when a design is truly ready to move from prototype to production, how to evaluate readiness through manufacturing reality rather than aesthetics, and how early alignment through industrial designer–manufacturer collaboration protects both creativity and timelines.

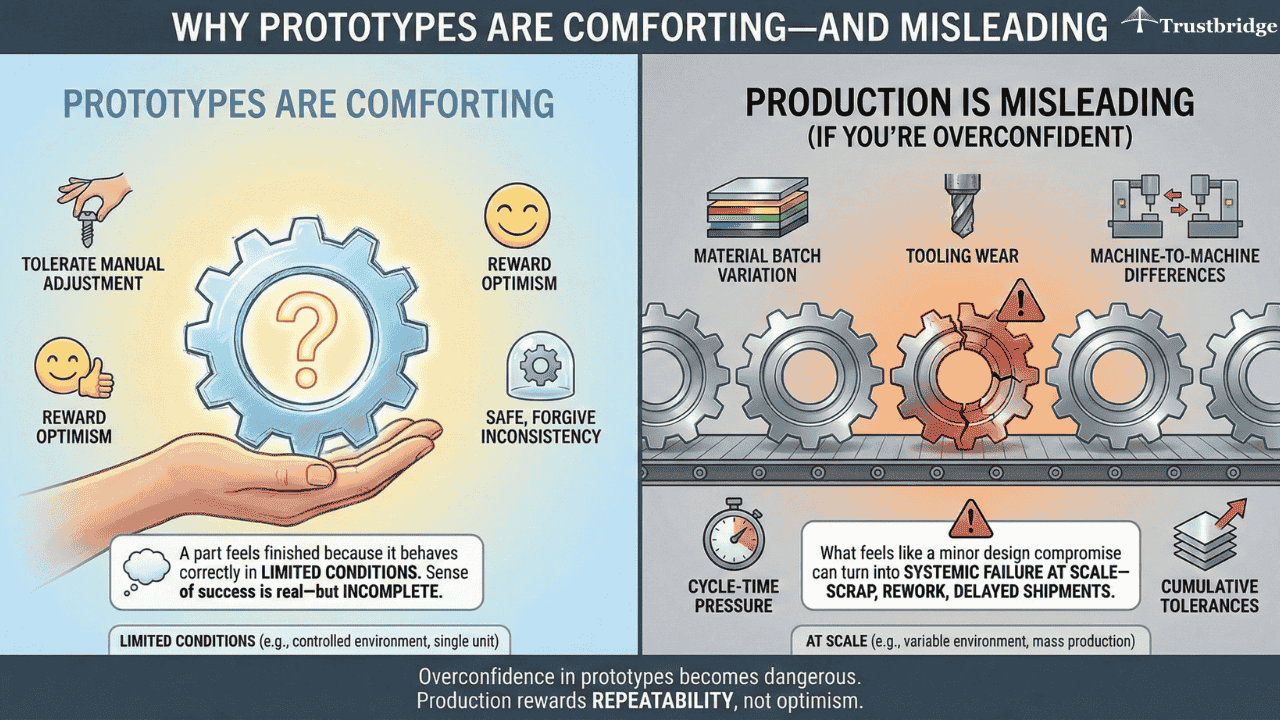

Why Prototypes Are Comforting—and Misleading

Prototypes are safe. They forgive inconsistency, tolerate manual adjustment, and reward optimism. A part that works in a prototype often feels finished because it behaves correctly in limited conditions. Designers test it, hold it, assemble it, and confirm that it meets functional intent. That sense of success is real—but incomplete.

Production does not reward optimism. It rewards repeatability. Manufacturing exposes variability that prototypes hide: material batch variation, tooling wear, machine-to-machine differences, cycle-time pressure, and cumulative tolerances across assemblies.

This is where overconfidence becomes dangerous. What feels like a minor design compromise during prototyping can turn into a systemic failure at scale—scrap, rework, delayed shipments, or field failures.

This is why the switch from prototype to production is not about asking whether a design works. It is about asking whether the design can work the same way hundreds or thousands of times without intervention. Designers who delay this shift often do so because prototypes continue to validate intent. What they are not validating is manufacturability.

The Real Question Designers Should Be Asking

The critical question is not “Can we make one?” It is “Can this be made consistently, predictably, and on schedule?” That question reframes the transition as a design responsibility, not a manufacturing hurdle.

At this stage, the role of the designer begins to change. Creative exploration gives way to decision ownership. Geometry choices stop being provisional. Materials stop being placeholders. Tolerances stop being inherited defaults. The design becomes a commitment with downstream consequences.

Prototype Iteration vs. Production Readiness

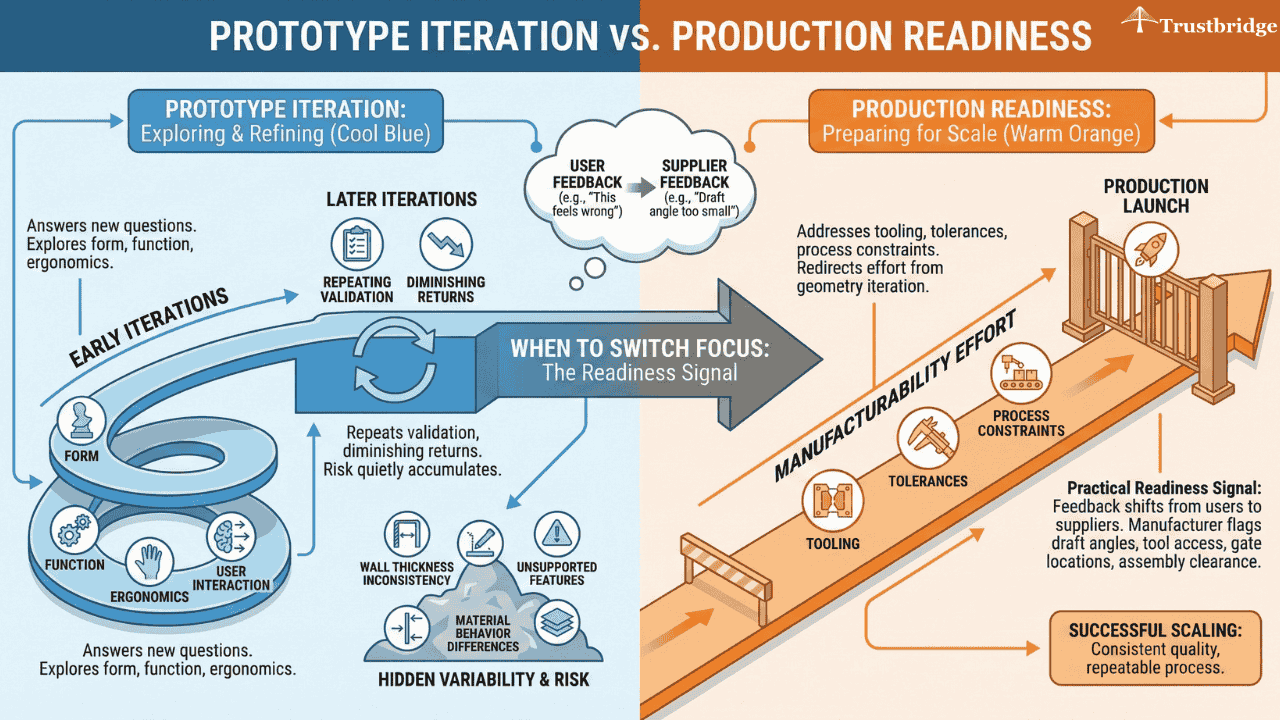

Iteration is valuable until it stops answering new questions. Early iterations explore form, function, ergonomics, and user interaction. Later iterations often repeat the same validation under slightly different conditions. This is where many teams get stuck.

When prototype iteration no longer reveals new insights about performance or usability, it is time to redirect effort toward manufacturability. Continuing to iterate geometry without addressing tooling, tolerances, and process constraints creates a false sense of progress. Designers feel busy, but risk quietly accumulates.

Common sources of hidden variability include wall thickness inconsistency, unsupported features, tight tolerance stacking, and material behavior that differs between prototype and production-grade resins or metals.

A practical readiness signal: when feedback shifts from users to suppliers. If manufacturers start flagging draft angles, tool access, gate locations, or assembly clearance, iteration has reached diminishing returns. That is the moment to switch focus.

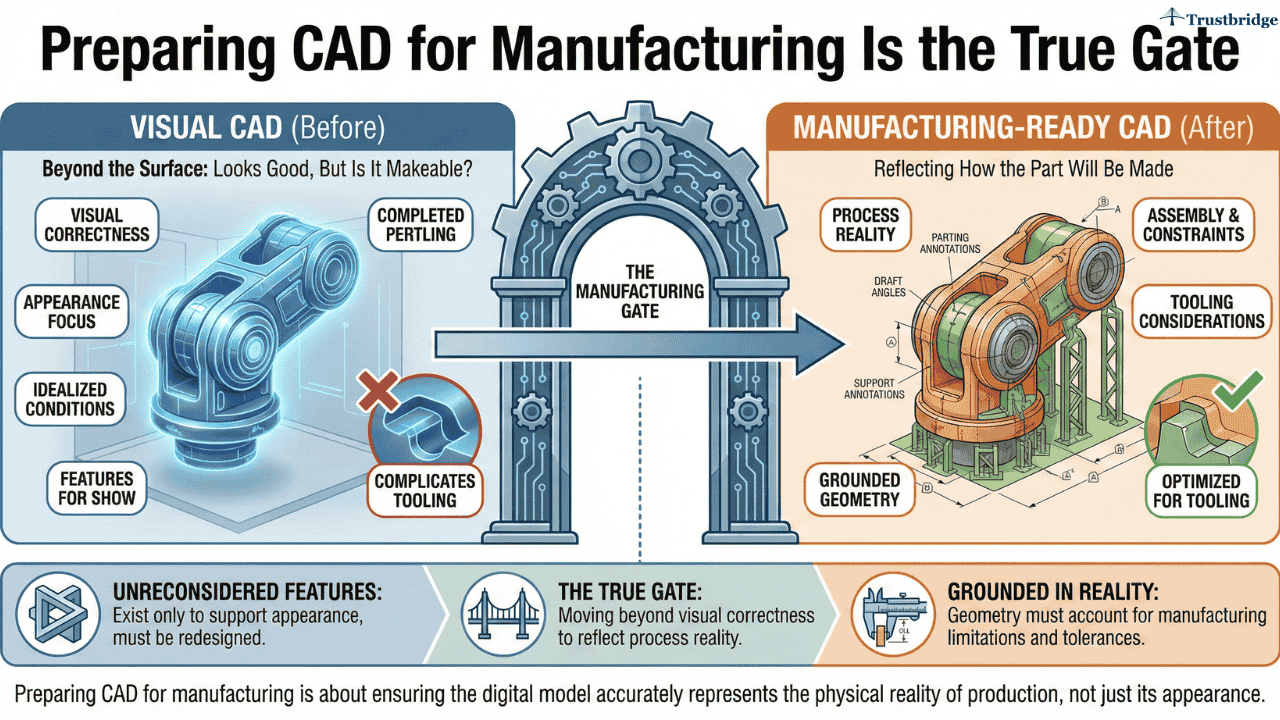

Preparing CAD for Manufacturing Is the True Gate

One of the clearest indicators that a design is ready to move forward is the state of the CAD. Early CAD models describe intent. Production-ready models describe behavior.

To prepare CAD for manufacturing, designers must move beyond visual correctness. The model must reflect how the part will be made, assembled, and constrained. Features that exist only to support appearance but complicate tooling must be reconsidered. Geometry that relies on idealized conditions must be grounded in process reality.

Sharp transitions that look clean on screen can cause stress concentration or tooling wear. Thin walls that pass prototype testing may lead to warpage, sink, or inconsistent fill in production. When CAD begins to account for these realities, it stops being a design sketch and becomes a manufacturing instruction.

Designers who invest in this transition reduce supplier pushback and shorten review cycles. Well-prepared CAD reduces ambiguity, accelerates tooling approval, and builds supplier confidence.

Design for Manufacturability Is Not a Checklist

Design for manufacturability is frequently misunderstood as a late-stage compliance exercise. In practice, it is a mindset shift that begins well before production tooling is ordered. For designers, DFM means making geometry decisions with an understanding of how materials flow, cool, shrink, and assemble.

Instead of asking whether a feature can be made, the question becomes whether it can be made repeatedly without special handling. Supplier feedback often highlights issues like unachievable tolerances, insufficient fillets, uneven wall thickness, or features that require secondary operations. These issues increase cost, risk, and lead time.

A simple DFM readiness check includes confirming tolerances intentionally, adding fillets for stress relief, validating wall thickness for injection molding, and removing features that demand manual intervention.

A common mistake is treating DFM feedback as a constraint rather than a design input. Designers who embrace DFM early discover that it does not limit creativity. It sharpens it. Constraints clarify intent and lead to solutions that scale.

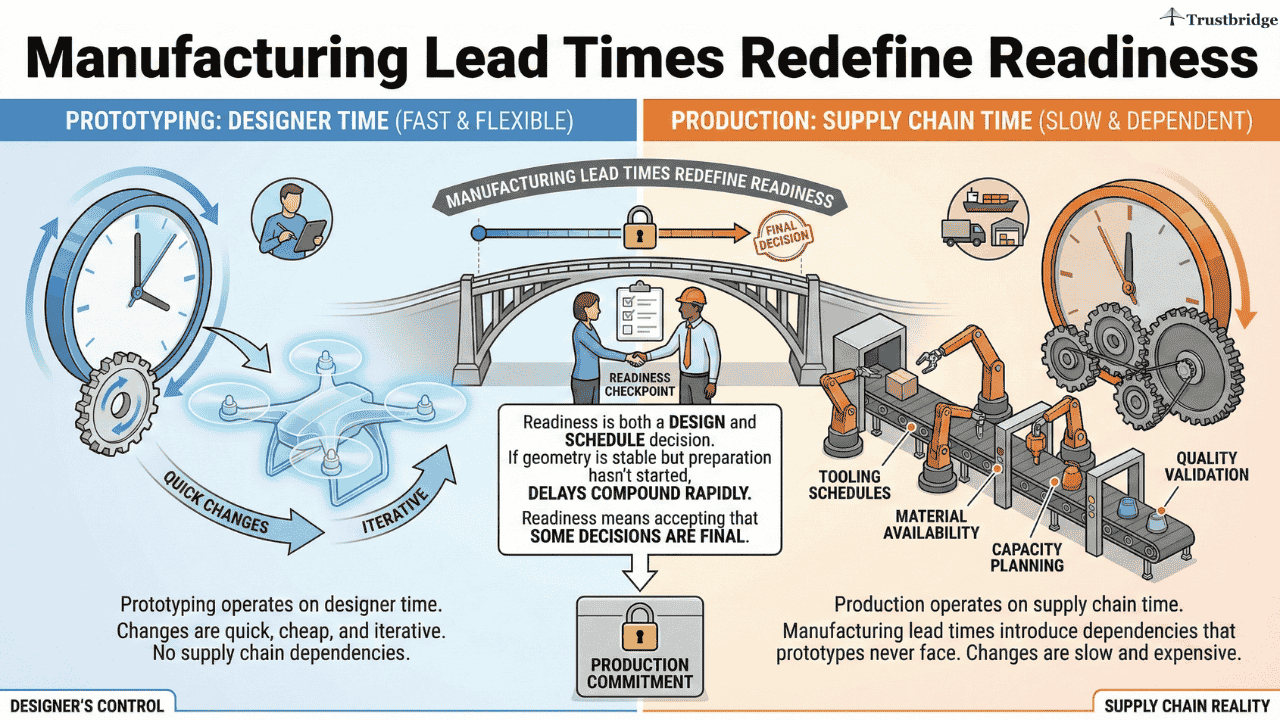

Manufacturing Lead Times Redefine Readiness

Prototyping operates on designer time. Production operates on supply chain time. This difference catches many teams off guard.

Manufacturing lead times introduce dependencies that prototypes never face: tooling schedules, material availability, capacity planning, and quality validation. Once production begins, changes are no longer quick—or cheap.

Designers who understand this treat readiness as both a design and schedule decision. If geometry is stable but manufacturing preparation has not started, delays compound rapidly. Readiness means accepting that some decisions are final.

Industrial Designer–Manufacturer Collaboration Is the Safety Net

No designer transitions successfully from prototype to production alone. Industrial designer–manufacturer collaboration is the strongest predictor of a smooth handoff.

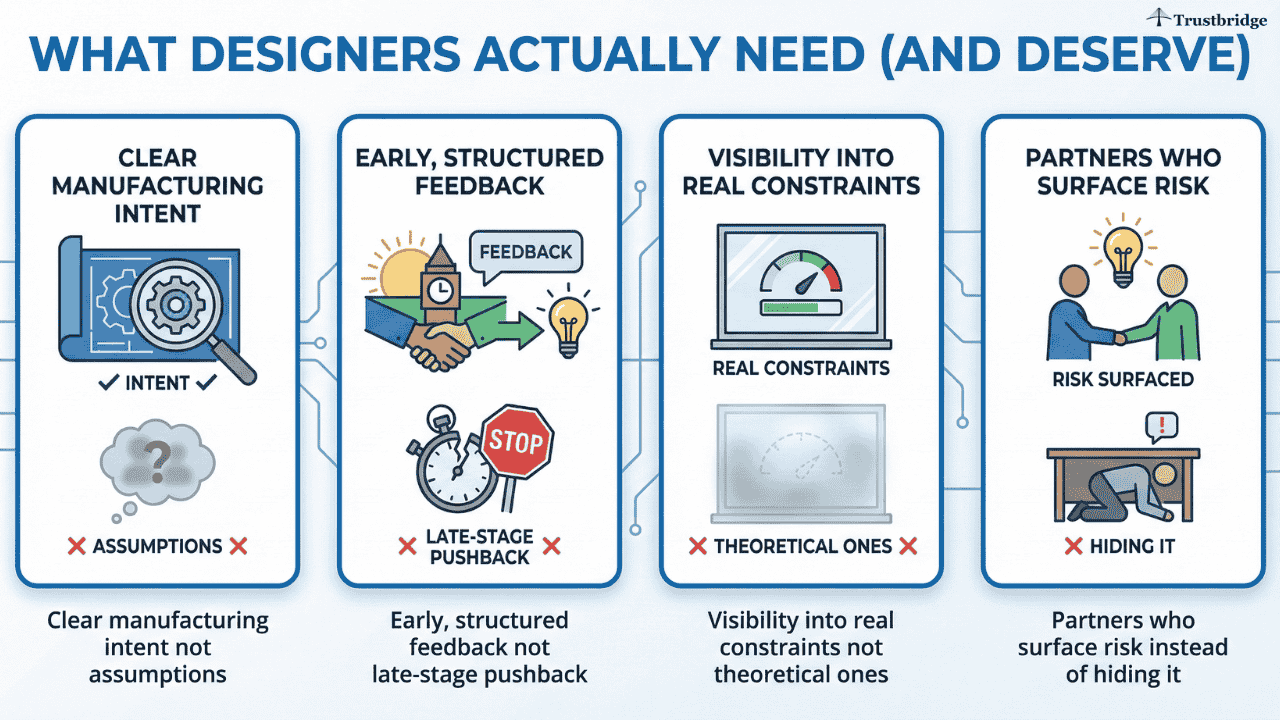

Manufacturers see problems designers cannot: tooling behavior, process limits, yield risk, and failure modes that never appear in prototypes. Early collaboration protects creativity by preventing late-stage compromises that dilute intent.

Real-world consequences of late collaboration include rushed tooling changes, unexpected cost increases, and missed launch dates. Early collaboration turns manufacturers into partners who help preserve design intent while enabling scale.

Actionable tip: involve manufacturing reviews while CAD is still flexible—not after it feels “finished.” That timing makes all the difference.

Trustbridge Tip: Moving from prototype to production isn’t just a design milestone it’s a supplier risk moment. As designs lock and volumes scale, uncertainty shifts from form to execution: lead times, compliance, capacity, and consistency. Digital procurement tools help teams reduce supplier risk at this exact transition point by bringing visibility into supplier performance, qualification status, and readiness—without slowing design or sourcing decisions. When designers and buyers share real-time insight into manufacturing capability, handoffs become cleaner and production ramps become predictable. To see how modern procurement platforms support faster, lower-risk decisions during scale-up, read our blog: How Do Digital Procurement Tools Help Buyers Reduce Supplier Risk Without Slowing Decisions?

Knowing You’re Ready to Switch

Designers know they are ready to move from prototype to production when uncertainty has shifted from design behavior to execution logistics.

At this stage, the remaining risks are not about whether the part works. They are about how quickly it can be produced, how consistently it performs, and how well intent survives scale. Those risks are best addressed through production preparation—not continued prototyping.

The decision is rarely comfortable. But delaying it rarely improves outcomes.

Conclusion: Readiness Is a Design Decision

The moment to switch from prototype to production is not defined by perfection. It is defined by clarity.

Designers who understand when to stop iterating, when to prepare CAD for manufacturing, and when to commit to design for manufacturability protect both their work and their timelines. Production is not where creativity ends—it is where intent is proven.

Design for Scale Before Scale Forces Your Hand

If projects stall between promising prototypes and painful production ramps, the problem is rarely effort. It is timing.

Switching from prototype to production requires alignment with manufacturing reality, early collaboration, and deliberate commitment. Design for scale early, and you gain speed, confidence, and fewer surprises later.

The strongest designs are not the ones that iterate the longest. They are the ones that are ready when it matters most.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why do so many products struggle when moving from prototype to production?

Because prototypes are designed to prove concept, not manufacturing reality. They tolerate loose processes, manual adjustments, and low volumes. Production introduces repeatability, tooling constraints, assembly forces, and manufacturing lead times that prototypes never reveal. The gap usually comes from design assumptions, not manufacturing failure.

2. How can designers tell when prototype iteration is no longer adding value?

Prototype iteration stops adding value when changes no longer reduce uncertainty. If each new prototype only confirms aesthetics or minor tweaks—but doesn’t address tooling feasibility, tolerances, or supplier feedback—it may be delaying production. That’s often the signal to shift focus from refinement to manufacturability.

3. What role does design for manufacturability play in deciding when to scale?

Design for manufacturability determines whether a design can survive real-world production. When geometry, tolerances, and materials are aligned with manufacturing processes, scaling becomes predictable. If manufacturability questions are still open, moving to production will amplify risk instead of reducing it.

4. Why is industrial designer–manufacturer collaboration critical before production?

Manufacturers expose constraints designers cannot see in CAD—tooling access, draft limitations, cycle times, and yield risks. Early collaboration ensures CAD is prepared for manufacturing and prevents late-stage redesigns that derail schedules, inflate costs, and erode design intent.