Thermoplastic Elastomer Materials (TPEs): A Design Guide for Flexible Components

The fastest way to lose design intent is to assume a flexible part will behave the same in production as it did in CAD or prototyping. Many industrial and product designers discover this too late after supplier pushback, tooling revisions, or a sudden loss of performance in production units.

If you are an industrial or product designer working daily in CAD, reviewing supplier feedback, and navigating late-stage redesign loops, flexible components are likely one of your biggest hidden risks. Parts that bend, grip, seal, or absorb impact often look resolved on-screen, yet behave very differently once they hit the factory floor.

Designing with thermoplastic elastomer material places designers at the intersection of user experience and manufacturing reality. Choices that feel minor during concept—wall thickness, transitions, tolerance assumptions—can later dictate whether a part scales cleanly or becomes a source of supplier pushback. This same gap between design intent and manufacturability is explored in depth in From CAD to CNC: Design Decisions for Manufacturability, where early design decisions are shown to directly impact downstream production success.

This guide is written explicitly for designers, not process engineers. It explains how TPEs behave across material selection in product design, design for manufacturability, how to prepare CAD for manufacturing, and how to move confidently from prototype to production through better industrial designer manufacturer collaboration.

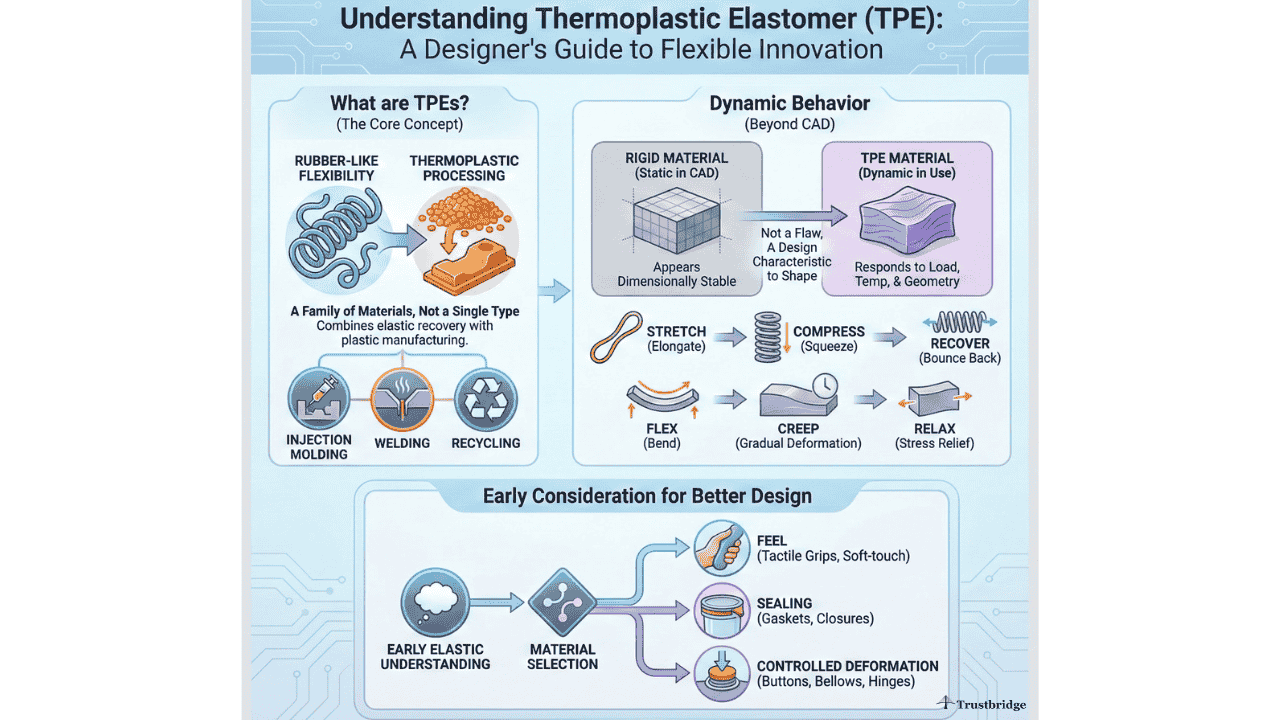

Understanding Thermoplastic Elastomer Material From a Designer’s Perspective

Thermoplastic elastomers, commonly referred to as TPEs, are not a single material but a family of flexible elastomers that combine rubber-like behavior with thermoplastic processing. For designers, this means parts can stretch, compress, and recover while still being injection molded, welded, or recycled like plastics.

Unlike rigid materials, soft elastomers respond dynamically to load, temperature, and geometry. A model that appears dimensionally stable in CAD may flex, creep, or relax once assembled or used. This behavior is not a flaw it is the defining characteristic designers must intentionally shape.

Early understanding of elastic behavior leads to better decisions during material selection in product design, especially for components that rely on feel, sealing, or controlled deformation.

Why Designers Choose TPEs for Flexible Components

Designers specify TPEs when flexibility is not optional but essential. Overmolded grips, seals, vibration dampers, soft-touch housings, gaskets, and snap features rely on controlled elasticity to function properly.

What makes thermoplastic elastomer material attractive is its ability to integrate flexibility directly into part geometry. Designers can eliminate secondary rubber components, reduce assembly steps, and create more compact products. However, these advantages only materialize when flexibility is designed into the part rather than added as an afterthought.

This is where design for manufacturability becomes inseparable from design intent. Flexible components amplify small mistakes. Inconsistent wall thickness, sharp transitions, or unsupported features can cause unpredictable deformation and inconsistent performance across production runs.

For example, designers often struggle with TPE overmolding adhesion and peel-off issues when the bond between the elastomer and substrate isn’t properly engineered. Multiple real-world projects experienced adhesion failure because the initial design didn’t account for material compatibility and surface preparation — a common scenario in consumer grips and soft-touch components.

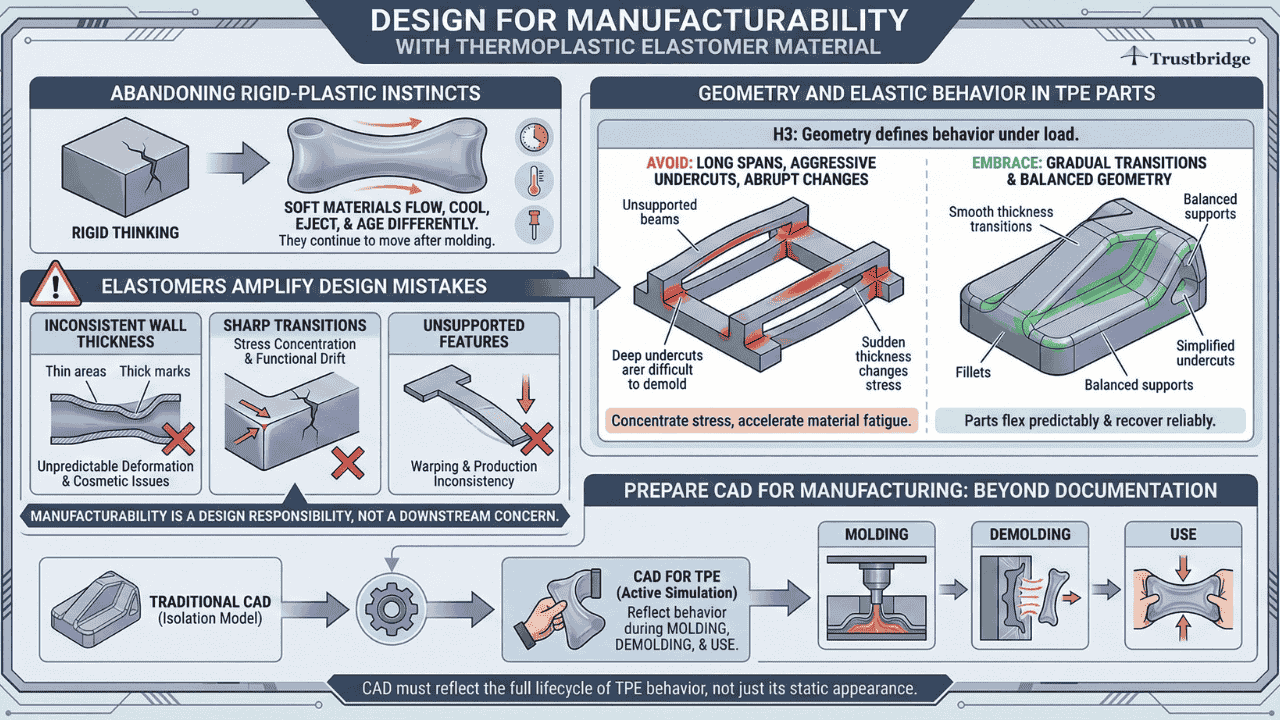

Design for Manufacturability With Thermoplastic Elastomer Material

Designing with TPEs requires designers to abandon rigid-plastic instincts. Soft materials flow, cool, eject, and age differently, and they continue to move even after molding is complete.

Parts made from elastomers amplify small design mistakes. Inconsistent wall thickness, sharp transitions, or unsupported features can introduce unpredictable deformation, cosmetic issues, or functional drift across production batches. This is where manufacturability stops being a downstream concern and becomes a design responsibility.

Geometry and Elastic Behavior in TPE Parts

From a CAD standpoint, geometry defines how a TPE part behaves under load. Long unsupported spans, aggressive undercuts, and abrupt thickness changes concentrate stress and accelerate material fatigue. Designers who respect gradual transitions and balanced geometry create parts that flex predictably and recover reliably.

This is why prepare CAD for manufacturing is not just a documentation step for TPE parts. CAD must reflect how the part will behave during molding, demolding, and use—not just how it looks in isolation. Many of these same CAD-to-production risks are addressed in How Designers Can Use CAD/CAM Software to Prevent Machining Errors Before Production Starts, where early validation helps eliminate costly downstream corrections.

Preparing CAD for Manufacturing With TPEs

Designers often assume that if a flexible part works in a prototype, it will work in production. With TPEs, this assumption is risky. Preparing CAD for TPE manufacturing means anticipating how softness, shrinkage, and elasticity interact with tooling and process conditions.

Tolerance Strategy for Flexible Components

A seal that “works” in CAD and early samples often fails in production because tolerances were inherited from rigid-plastic habits. Elastomers compress, relax, and respond to temperature, making tight tolerances both unnecessary and risky.

Designers should define tolerances by function rather than convention. Compression interfaces benefit from controlled interference, while cosmetic dimensions should allow flexibility. Clear intent here reduces supplier confusion and improves <b>industrial designer manufacturer collaboration.Example:

A practical case is sealing interfaces where parts appear to seal nicely in early samples but fail later because elastomers compress and relax differently than rigid plastics. Wang’s industry insights report how suction and adhesion issues often emerge only during full-scale production when TPE geometry and material interactions are stressed

Surface Finish and Part Interaction

Surface texture directly affects grip, friction, and perceived quality. Soft materials exaggerate texture and reveal defects more easily than rigid plastics.

Preparing CAD with realistic surface expectations protects design intent and prevents mismatches between what designers specify and what manufacturers can reliably deliver.

From Prototype to Production with Thermoplastic Elastomer Material

This transition is where most TPE designs fail, not because of manufacturing, but because of design assumptions.

Prototypes are misleadingly forgiving. They tolerate uneven cooling, generous process margins, and low-volume adjustments. Production exposes true material behavior under cycle time pressure, thermal stability, and repeatability constraints.

Designing for scale is not a manufacturing job alone. When designers treat prototype to production as a continuous design responsibility, late-stage surprises decrease dramatically.

Trustbridge Tip: Designing flexible components with thermoplastic elastomer materials requires more than just great CAD models, it requires thinking like production from day one. Successful TPE parts anticipate tooling behavior, material elasticity, and scale effects long before the first prototype is run. That means integrating design for manufacturability early, validating geometry against real production constraints, and aligning supplier capabilities with your design intent. To see how a robust CAD-to-production mindset accelerates delivery and reduces redesign cycles, read our blog: From CAD to Production: How Design for Manufacturability Defines Success.

Why Industrial Designer–Manufacturer Collaboration Is Critical for TPE Success

Flexible materials amplify the cost of miscommunication. Successful TPE components are rarely designed in isolation. Strong industrial designer manufacturer collaboration allows designers to understand tooling constraints, gating strategy, parting lines, and expected material behavior before finalizing geometry.

Manufacturers bring insight into mold design, material grades, and processing windows. Designers bring intent, user requirements, and aesthetic priorities. When these perspectives align early, TPE parts perform better and reach production faster.

Example:

In overmolding design, adhesion failures are a known challenge when the TPE bond is assumed rather than engineered. Real-world examples include projects where TPE peeled off substrates because material compatibility wasn’t validated early, requiring redesigns with primers or mechanical interlocks for durable adhesion.

Design for Manufacturability as a Creative Advantage

Designers who understand manufacturing reality gain more creative freedom, not less. Mastery of elastomer behavior allows flexibility to be used intentionally rather than defensively.

This is where design for manufacturability becomes a creative advantage—enabling integrated functions, simplified assemblies, and more expressive forms without sacrificing scalability.

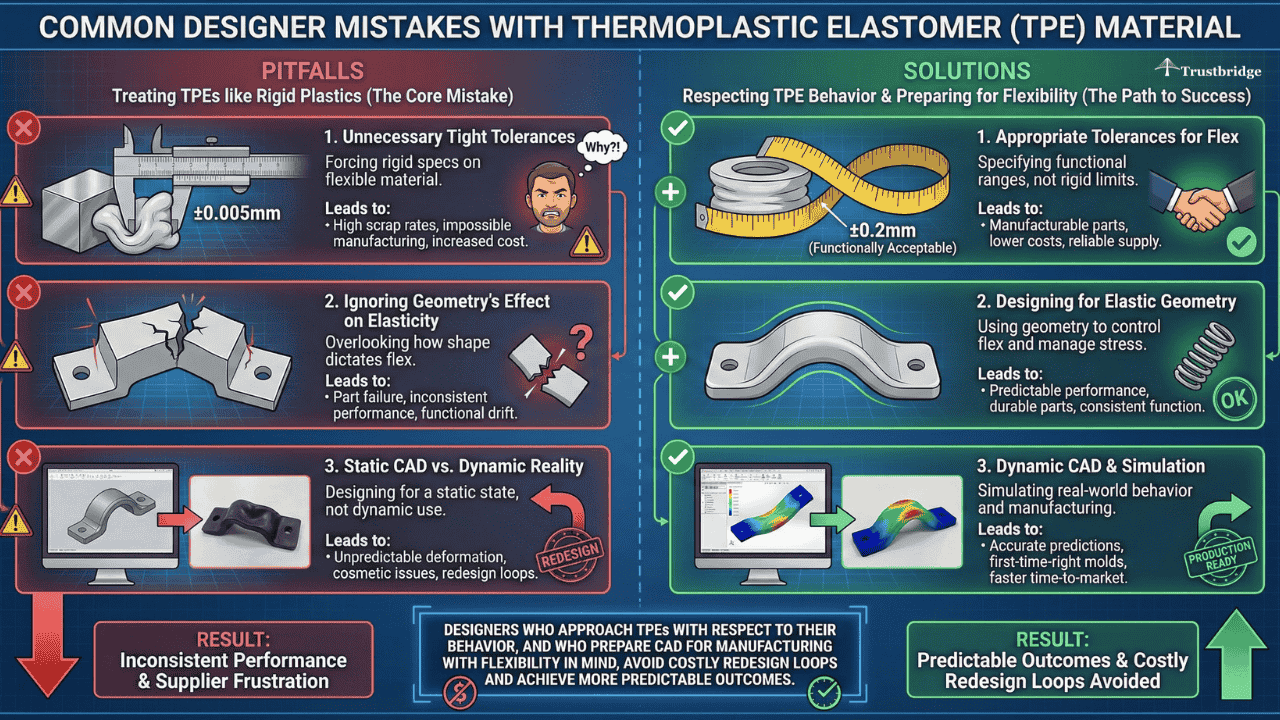

Common Designer Mistakes with Thermoplastic Elastomer Material

Most TPE failures trace back to early design assumptions. Treating TPEs like rigid plastics, specifying unnecessary tight tolerances, or ignoring how geometry affects elasticity leads to inconsistent performance and supplier frustration.

Designers who approach TPEs with respect to their behavior, and who prepare CAD for manufacturing with flexibility in mind, avoid costly redesign loops and achieve more predictable outcomes.

Conclusion: Designing Flexible Components That Scale

Thermoplastic elastomers offer designers immense opportunity, but only when used intentionally. Choosing thermoplastic elastomer material is not just a materials decision; it is a commitment to thoughtful material selection in product design, strong design for manufacturability, and proactive collaboration.

Designers who understand how to move from prototype to production, align early through industrial designer manufacturer collaboration, and prepare CAD with manufacturing reality in mind create flexible components that perform consistently and scale confidently.

Great flexible design does not stop at comfort or aesthetics. It succeeds when the factory can reproduce it reliably, repeatedly, and profitably.

If you are tired of late-stage redesigns, supplier pushback, or watching carefully crafted design intent erode during manufacturing, the solution starts earlier than most projects allow. Design flexible components with scale in mind, align with manufacturing before geometry is frozen, and treat production behavior as a design input—not a post-design surprise. Flexible designs are powerful. Designing them for manufacturing is what protects your intent.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common CNC Machine & Programming mistakes shops make?

The most frequent issues include incorrect work offsets, improper CNC tool selection, missing simulations, wrong speeds and feeds, and poor fixturing. These errors often lead to tool crashes, scrap machined parts, and wasted cycle time.

2. How much impact does skipping CAM simulation really have?

Skipping simulation is one of the costliest mistakes. Without proper toolpath verification, programmers may miss collisions, gouges, or holder interference especially in 4-axis and 5-axis jobs. A single missed step can destroy tooling, scrap expensive parts, and cause machine downtime.

3. Why is correct CNC tool selection so important?

Choosing the wrong CNC tool, such as incorrect flute count, tool coating, or geometry can cause chatter, poor chip evacuation, premature wear, and poor surface finish. Using manufacturer recommendations and maintaining a standardized tool library significantly improves program reliability.